Toxic Phosphorus and Swedish Matches: The Dangerous Path to Safe Fire

From natural flame to human control

The fire discovered by humans dates back possibly half a million years. Yet it was the exit from the Stone Age—enabled by fire for metal processing—that arrived roughly six thousand years ago. Fire also reshaped our distant ancestors: cooked meat reduced the need for robust teeth and massive jaws.

At first, flame was born from nature: lightning, volcanic eruptions, and spontaneous combustion of dry grass. Later, people learned to harness fire through friction—sparking stones or rubbing dry sticks together. The biggest challenge was not creating fire but preserving it, a responsibility that took on a sacred, priestly role.

Stone, even flint, remained a source of fire for centuries when paired with metal (fire steel) and tinder—dried fungi, sulfur-dipped splints or wicks, or accordion-folded paper that became common by the 18th century. Modern lighters still echo these ancient elements (stone, steel, tinder) and conceptually predate the chemical match.

Chemistry lights the way

The first chemical lighter was invented by German chemist Johann Wolfgang Döbereiner, an avid smoker better remembered today for his connection to Goethe. Döbereiner observed that hydrogen in air could make platinum glow—a phenomenon we now call catalysis. This led to a lighter with a grand name—“sparkling machine,” “fire and light producer,” “dynamic igniter.”

Cumbersome by modern standards, it required generating hydrogen in a vessel with zinc and sulfuric acid, then applying a spongy platinum substitute as tinder. Despite the inconvenience, Goethe famously used it with delight and even sent the inventor a letter of thanks.

The birth of the match

The chemical match traces to the late 17th century, when Robert Boyle experimented with newly discovered phosphorus (alchemist Hennig Brand obtained it in 1669 from dried urine). Boyle’s assistant, Francis Hauksbee, ignited sulfur-dipped splinters by rubbing them with phosphorus—dangerous and expensive at the time.

A key breakthrough came in 1786 with the discovery of potassium chlorate by French chemist Claude-Louis Berthollet. In 1805, another Frenchman, Jean Chancel, created a sulfur splinter whose head—potassium chlorate mixed with sugar—ignited when dipped into an asbestos container soaked with sulfuric acid. It was the first chemical match: not ideal, but a leap beyond flint and steel.

In 1827, English pharmacist John Walker of County Durham began selling sulfur splinters tipped with antimony sulfide and potassium chlorate. They ignited—sometimes explosively—when struck on sandpaper. Walker called them “Congreves,” and he became an official supplier to King William IV.

Walker’s priority is sometimes disputed: Germans cite Moldenhauer’s patents, Austrians mention Preshel and Röhner, and Italians point to Piedmont botanist Gidliano. Two stories stand out. Jakob Friedrich Kammerer of Germany reportedly invented matches in prison, tried to commercialize them, was accused of witchcraft, saw his house burned down, and died in poverty. Italian Sansone Valobra, who fled Piedmont after the 1821 uprising, developed phosphorus-headed sulfur matches in Naples.

Toxic phosphorus and the push for safety

Improved matches thrilled consumers, but white phosphorus used in manufacturing proved toxic for workers. Although sesquisulfide phosphorus, invented in 1864 by Lemoine, was far safer, adoption lagged for decades. In 1906, the Berne Convention banned white phosphorus; some nations enforced the change later, and in the United States, high tariffs on such matches produced a similar effect without a formal ban.

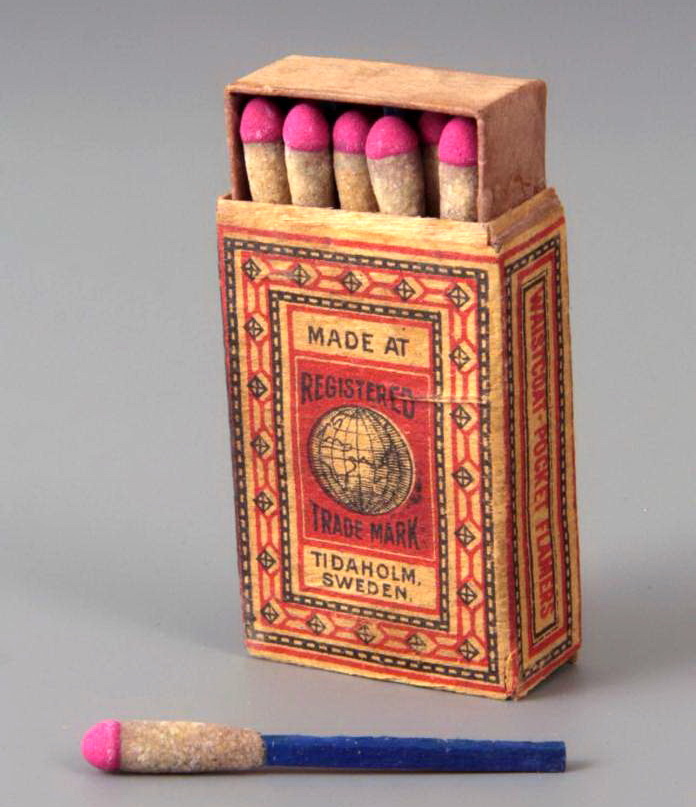

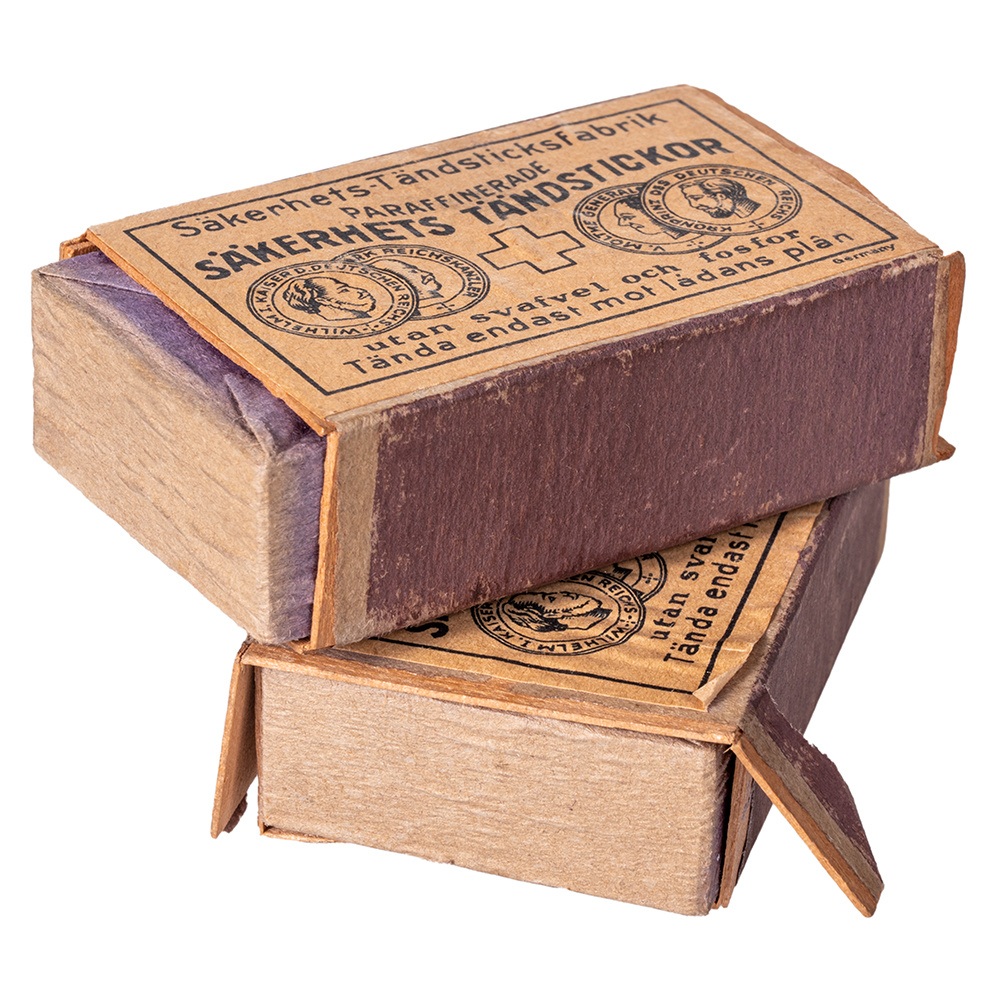

French engineer Charles Sauria is often credited with quiet, safer matches by mixing potassium chlorate with white phosphorus. In 1844, Swedish chemist Gustaf Erik Pasch patented red phosphorus, paving the way for true “safety” matches. Production took off under fellow Swede Johan Edvard Lundström, whose Jönköping factory became an industry center.

Two families of matches emerged: ordinary matches (igniting on many rough surfaces) and “Swedish” safety matches (igniting only on a specially prepared striking surface). Wax matches also appeared—likely an Italian innovation, possibly by Valobra—and were produced in Naples until 1835.

How matches are made

Wooden matches, typically cut from poplar, are treated with ammonium phosphate to prevent coal scattering. Heads combine combustibles (such as sesquisulfide phosphorus or sulfur), oxidizers (like potassium chlorate), and inert fillers to moderate burn rate. Wax matches are formed from paraffinated paper.

Quality control focuses on strength, sensitivity to ignition, and moisture resistance. Modern production lines are highly automated and require minimal manual labor.

For smokers: the ritual of the light

From flint sparks to safety matches, the simple act of making fire shaped the ritual of lighting a cigarette. Many adult smokers still appreciate the clean, even burn a good match can offer—especially outdoors or when wind makes a lighter finicky.

If you’re here to stock up on your favorite brands, explore our selection at cigsspot.com/shop. Want to know how we measure up? See recent customer feedback on Trustpilot.

- You might also like: Why smoking on planes went away

- Shop premium cigarettes with fast, discreet delivery

Bottom line

From ancient embers to modern safety matches, humanity’s path to portable fire is a story of ingenuity, chemistry, and public health. The matchbox in your drawer carries centuries of trial, error, and innovation—one more reason the simple spark still feels a little bit magical.

Disclaimer: This article is for historical and educational purposes only. Always use fire responsibly and follow local laws and safety guidelines.